Loitering Airborne Systems

Loitering munitions provide eyes in the sky for target acquisition as well as lethal firepower. Has their time finally arrived?

Giulia Tilenni

05 March 2018

Loitering munitions (LMs) were first introduced in the 1980s to designate a type of unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) able to carry out strike missions, thanks to an explosive warhead. Loitering munitions merge missiles and a UAV’s capabilities. The munition is usually canister/catapult launched, guided by a ground-based operator (even if they have a certain degree of autonomy) and equipped with high-resolution electro-optical infrared cameras.

Loitering munitions’ intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance (ISR) capabilities help the operator identify potential targets. They can autonomously detect pre-identified targets thanks to seekers, but the munition will only hit its target if commanded by the operator. Man-in-the-loop capabilities are critical for avoiding collateral damage and/or false target identification. Furthermore, the low magnetic signature and the service ceiling make LMs difficult to detect, which makes them ideal for asymmetric warfare in urban scenarios.

Despite their potential on the battlefield, LM’s use, so far, has been limited. To date, users include Azerbaijan, China, Germany, India, Israel, Kazakhstan, South Korea, Turkey, the US and Uzbekistan. A deployment of loitering munitions on the battlefield was reported in 2015 and 2016 in Nagorno-Karabakh in the South Caucasus.

The use of LMs remained limited until 2010, both in terms of users and available models. For approximately 10 years, Israel Aerospace Industries (IAI) MBT missiles division’s Harpy and Harop were the most used LMs. Harpy could carry a 32 kg warhead and fly six-hour long missions within a 500 km range.

INTELLIGENCE AND FIREPOWER

More recently, the use of LMs has experienced somewhat of a renaissance. As the battlefield becomes more dangerous and budget constraints arise, LMs make a great addition to available military assets for two reasons. Firstly, the array of missions LMs can be used for is broadening. In addition to Suppression of Enemy Air Defence (SEAD) tasks, LMs can now destroy static and mobile targets, while sending back ISR output, thanks to their optronic sensors. ISR missions can be performed alone or to better support strike missions.

Secondly, the miniaturisation of warheads radically changed the role of LMs. In the beginning, they were mainly used for strategic missions. Today, LMs can provide intelligence and firepower to tactical groups/land forces and special forces.

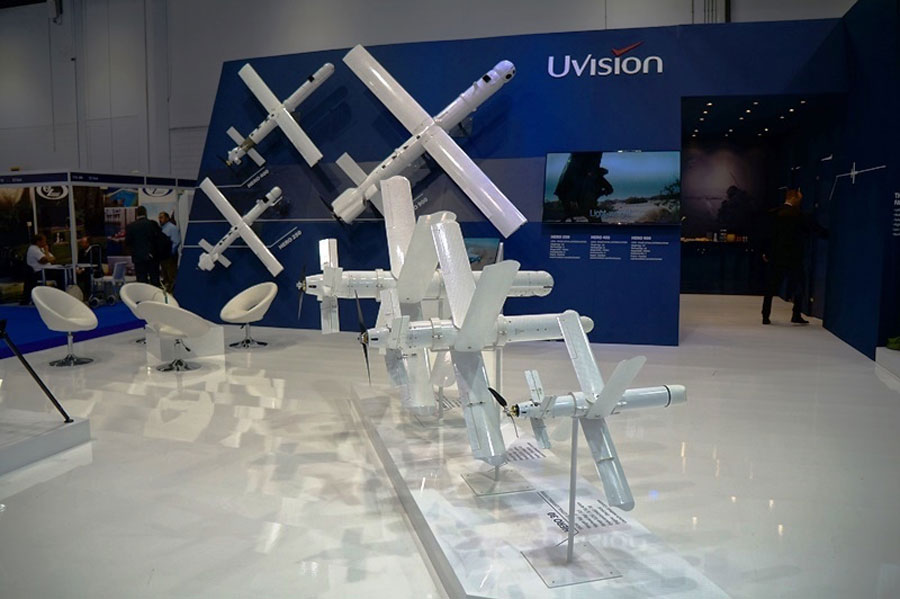

The interest in procuring LMs is increasing and the number of off-the-shelf models is growing accordingly. The most notable example of LMs’ versatility is the Hero family, launched by Israeli firm UVision at the 2015 Defence and Security Equipment International exhibition in London. It has since been expanded and upgraded.

The Hero family consists of 8 LMs, each with a different use case: from the tactical Hero 30 (man-pack portable, 0.5 kg warhead, 30 min endurance) to the strategic Hero 1250 (30 kg warhead within a 200 km line-of-sight range). The newcomer is the Hero 400EC, a 10 kg warhead LM, which can provide high-speed transit and low-speed loiter thanks to an electric engine.

IAI introduced new LM products, namely the Harpy NG (an anti-radar system equipped with a radio frequency seeker, six-hour endurance, 1,000 km maximum range, 15 kg warhead) and the tactical LMs Green Dragon (1.5 hr endurance, 40 km maximum range, 15 kg weight, 3 kg warhead) and Rotem (30–45min endurance, 10 km maximum range, 1 kg warhead).

However, other producers are now eyeing the LMs market. In February 2017, China National Aero-Technology Import & Export Corporation displayed the model of a Harpy-inspired LM, the ASN-301. The two models are reported to share the same weight (139 kg) and four-hour endurance, but the ASN-301 has a shorter range (288 km).

At the end of 2017, Polish company WB Group was awarded a contract to provide 1,000 Warmate tactical LMs to the Polish land, territorial defence and special forces. These nationally produced LMs, which are available in three payload configurations (EO/IR, EO-fragmentation charge warhead, EO-linear cumulative charge warhead), have a 10 km range and 30-minute endurance.

The Turkish company STM is delivering to Turkey’s Special Forces the first batch of the domestically-produced fixed-wing Alpagu LM (5 km range, 10-minute endurance, 3.7 kg weight). Another LM from the same producer, the rotary wing Kargu (5 km range, 10-minute endurance, 6.3 kg weight) is expected to enter service soon. The STM-produced LMs mirror today’s most used tactical LMs within the US Armed Forces, the AeroVironment Switchblade (10 km range, 10-minute endurance, 2.5 kg weight).

Now that LMs can be used for a variety of missions, it is likely that the number of solutions and users will expand in the coming years, as LMs provide cheap, yet accurate fire support to troops. Further developments are expected in terms of operational environments and carriers (at DSEI 2017, IAI unveiled the Maritime Harop, which can be launched from different platforms), swarming and manned/unmanned collaboration. However, the use of LMs has some risks as well. LMs’ growing autonomy will negatively impact the possibility to abort a mission to avoid errors or collateral damage. Secondly, non-state actors have also expressed an interest in acquiring LMs, raising the chances of the technology being used maliciously.

THE UK AND LOITERING MUNITIONS

In 2007, Team LM (a group of small and mid-sized companies, academia and other defence companies, led by MBDA) unveiled its Fire Shadow loitering munition. According to official statements published by MBDA, “the weapon system [was] presented as a solution for the UK ground forces’ requirement for a low-cost, all-weather, 24-hour capability to carry out precision attacks against surface targets, which may be difficult to engage and time-sensitive.”

A Fire Shadow start-up capability (25 units) was expected to enter service with British forces in 2012 in Afghanistan. However, despite performances of the hardware meeting the desired requirement, the success rate was lower than expected. As a result, “the Senior Responsible Owner took a decision not to deploy the weapon for testing in Afghanistan as the capability was not sufficiently mature,” British official documents state.

In fact, Fire Shadow never entered service with the British Army. In 2017, MBDA proposed the Fire Shadow to Poland, but the system was not selected.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Giulia Tilenni is a junior analyst in defence and security affairs and editorial co-ordinator of the European affairs desk at Il Caffè Geopolitico, an online journal of international politics. She provides analysis on UAVs, military intelligence and EU defence issues.

This article is taken from the Winter 2017/2018 edition of Defence Procurement International. To obtain a copy of the magazine, SUBSCRIBE here.