Protected on the outside, but not the inside

Jonny Mortimer Hendry, a former Captain in the Parachute Regiment, is competing in the 250 km Marathon des Sables wearing body armour, to raise awareness of soldier's mental health.

Anita Hawser

16 March 2022

It was 18 February 2022, and as Storm Eunice closed in on the UK with wind speeds of up to 80 miles per hour, Jonny Mortimer Hendry, a former Captain in the British Army’s Parachute Regiment, was running through the streets of south London battling strong head winds with 10 kg of body armour strapped to his chest.

“I got some odd looks in the gym,” says Mortimer Hendry, where he spent 20 minutes doing press-ups before finally entering the sauna. “I was trying to acclimatize myself,” he says.

On the 24 March, Mortimer Hendry will take part in one of the toughest races on earth, the Marathon des Sables in Morocco, a 250 km stretch across the Sahara, which participants must complete in just seven days, carrying everything they need to survive in the hot and dry conditions on their backs.

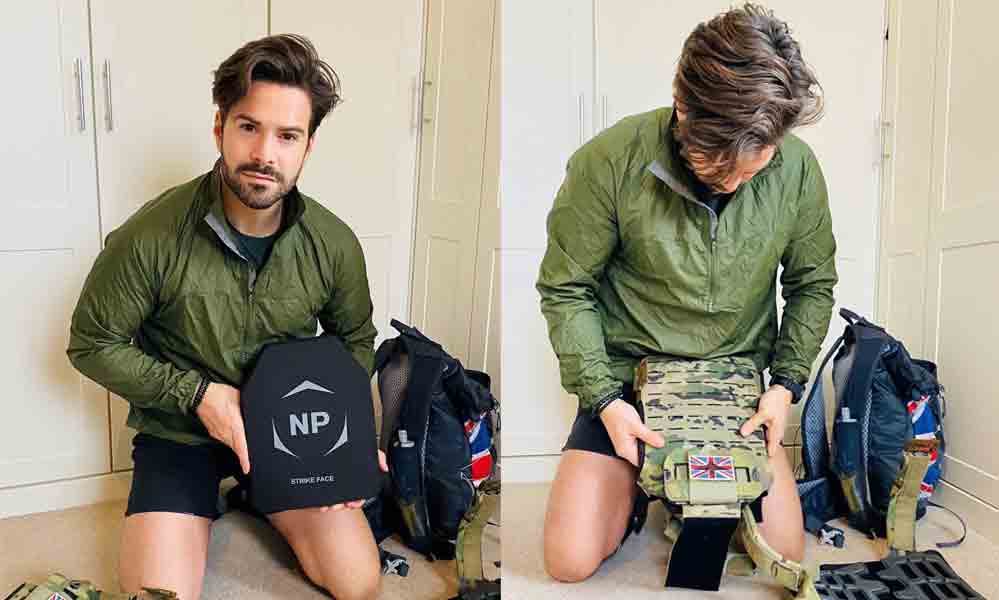

In addition to his 10 kg backpack containing food and water, and whatever else he needs to survive on the long, arduous journey, Mortimer Hendry will also be wearing 10 kg of heavy-duty body armour — two plates front and back — made from composite ceramics, which can withstand bullets from high-powered sniper rifles. The armour is supplied by NP Aerospace, a Coventry-based company, best known for manufacturing the body armour plates and armoured vehicles used by UK armed forces in Afghanistan.

Mortimer Hendry not only has his sights set on a new Guinness World Record — he will be the first person to compete in the Marathon des Sables wearing body armour — but he also hopes to raise £50,000 for the UK's Support Our Paras charity, which provides equipment, financial support and assistance to serving soldiers and veterans from the Parachute Regiment and Airborne Forces to help them transition into full-time employment after they leave service.

As a former Captain in the British Army’s D Company, 2nd Battalion Parachute Regiment, Mortimer Hendry completed numerous operational tours in Afghanistan, so body armour must almost feel like a second skin to him. But this time around, wearing it holds special significance. “When you go to war your body armour protects you against bombs and bullets, but nothing protects your mind,” says Mortimer Hendry. “I am running the Marathon des Sables to make a powerful statement about soldiers' and veterans' mental health and to encourage others to seek help to overcome their battles. "Whilst serving in the Paras, I was involved in incidents that I struggled to process upon his return, but with the help of Support Our Paras, I was able to find therapy and get his life back on track."

The most dangerous place on earth

Am I going to be able to do my job Having joined the Army in 2008, Mortimer Hendry deployed on his first operational tour when he was 20-years old. Destination: The Green Zone in Helmand Province Afghanistan, one of the most dangerous places on earth. He was based there for six months on, six months off, from 2010 to 2012, which were the main fighting years in Afghanistan. The operational tempo was like nothing he had ever experienced before. “I was going, coming back, going, coming back and a lot of the mental health issues stemmed from that period of time,” he explains. “It was easy to overlook it as it was incredibly high-tempo operations, and I didn't have time to focus on it.”

Mortimer Hendry always seemed destined for a career in the Army. At 16, he was awarded a scholarship to the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, where he was commissioned into the Parachute Regiment. While his mates were running round getting drunk at university, he was preparing his body and mind for becoming a soldier. “The physical aspect of training is really important and is linked to mental health,” he says, “but nothing really prepares you for the realities of war.”

As a young platoon commander going out to Afghanistan at the height of the military campaign, he spent long periods of time waiting for things to happen. Then next thing he knew, he was suddenly in the middle of a fire fight. “You then start thinking, 'Am I going to be able to do my job as a unit commander? Are the guys going to listen to me? Am I going to be able to deliver? I don't want to let anyone down.' We started sustaining casualties fairly quickly from IED blasts. One of the guys lost his arm, which made it real, and it carried on in that vein really.”

Making the rank of Captain at 23, Mortimer Hendry ended up serving in some specialist units in Afghanistan. In 2009, a year after he'd deployed to Afghanistan, the first up-armoured Mastiffs and Ridgeback protected patrol vehicles were deployed by the British Army to Afghanistan for operations in troubled Helmand Province.

“When the British Army first entered Afghanistan, they were using Snatch Land Rovers from the 1990s, which were not designed to take IED blasts,” says James Kempston, CEO, of NP Aerospace. “They were used well beyond their capabilities. NP Aeropace won a contract, which came out of a UOR, to deploy new vehicles fast to protect our soldiers out there. We deployed Mastiffs within six months. These vehicles saved countless lives and protected the war fighter. We really do care about what we do and why we do it. Ultimately, these vehicles protect lives.”

For Mortimer Hendry, protected mobility was the main way of getting around in Afghanistan. He felt protected on the outside — a Mastiff can easily take a large IED blast — but mental health wasn't a topic that was widely discussed within the Army, he says. “I spent 2010-2012 on operations on the frontline and when I came back from that it was like an almighty hangover. Three years on operations I didn't know the debt my mind would pay, which caused me a few issues.”

Mortimer Hendry packs his heavy duty armour in preparation for the Marathon des Sables: When you go to war, you wear stuff to protect your body, but not your mind.

He didn't even get time to process the loss of his friend. Before he knew it, he had picked up his stuff from his barracks in Colchester and was headed to another unit. “Four months later, I was back in Afghanistan as team commander of a different unit on another kinetic tour. We took casualties, but it wasn't until I came back from that. I was 25 and felt like I had lived a whole life. It felt like I'd had the passion and enjoyment sucked out of me. I was in this briefing room and I had to take myself outside. I was retching, and one of the Senior Officers came outside and said to me, 'I know what you need. You need to speak to someone.'”

Mortimer Hendry was referred to someone within his unit at Merville Barracks in Colchester. “I hadn't talked about how I felt to anyone," he says. "I remember turning to go down a road and I lost my mind with rage. I experienced extreme highs and lows. Then I realised if I didn't deal with this now, I'd have to deal with it when I was like 40 or 50.” Mortimer Hendry says if his story is anything to go by, people are struggling to find help and resources. “The last couple of years has been horrendous for a lot of people, so I want to use my experience as a conduit to talk about mental health, and do something positive and empowering,” he says.

Stories like this are quite common among military personnel returning from service, says Kempston of NP Aerospace. “Some of the things they experience are tough to process. Armour protects the body, but we don't make things to protect the mind. The military isn't just about fighting, but about making sure people can get back to life after they have been deployed.”

In addition to NP Aerospace, organisations supporting Mortimer Hendry on his epic Marathon des Sables journey, include Edgar Brothers, BeaverFit UK, Firepot, and Support Our Paras.

For further information about Support Our Paras visit https://supportourparas.org/

To make a donation to Jonny's Marathon Des Sables in Body Armour 2022, visit: https://www.justgiving.com/fundraising/jonny-hendry