The March of the Robots?

The Royal Navy wants an unmanned capability for routine mine countermeasures in two years. But don't write off the traditional mine hunters just yet.

Anita Hawser

25 September 2017

As traditional minehunter vessels reach the end of their operational life, navies are exploring new concepts that feature an array of unmanned systems for stand-off mine countermeasures. Belgium and the Netherland’s bi-national concept for future mine countermeasures (MCM) is divided into two main components: a MCM toolbox, which will include a variety of subsurface, surface and air domains—unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs), unmanned surface vessels (USVs), unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), very shallow water and explosive ordnance disposal modules; and the MCM platform (the means for transporting for the MCM systems).

The OCCAR-EA Maritime Mine Counter Measures (MMCM) Programme between the French Navy (Marine Nationale) and the UK's Royal Navy will develop a prototype/ demonstrator to determine the feasibility of using unmanned surface and underwater systems, with effective command and control, to detect and dispose of mine threats.

At DSEI in London in September, First Sea Lord Admiral Sir Philip Jones said that an unmanned system for mine countermeasures would be deliverable in the next two years:

“We are ready to shift the process of trial and experimentation from the exercise arena to the operational theatre ... I can announce the Royal Navy’s aim to accelerate the incremental delivery of our future mine countermeasures and hydrographic capability (MHC) programme. Our intention is to deliver an unmanned capability for routine mine countermeasure tasks in UK waters in two years’ time.”

First Sea Lord — Admiral Sir Philip Jones

The demand for unmanned systems is largely being driven by the desire to keep naval assets and crew safe by enabling them to operate at a safer distance from the minefield. The cost of maintaining traditional minehunter vessels and the desire to clear mines more quickly using unmanned systems, are also contributing factors.

Navy decision-makers want to keep the man out of the minefield. But how do the crews of traditional minehunter vessels feel about unmanned systems doing more of the work? At DSEI in London recently, we got the opportunity to visit one of the Royal Navy’s traditional minehunter vessels.

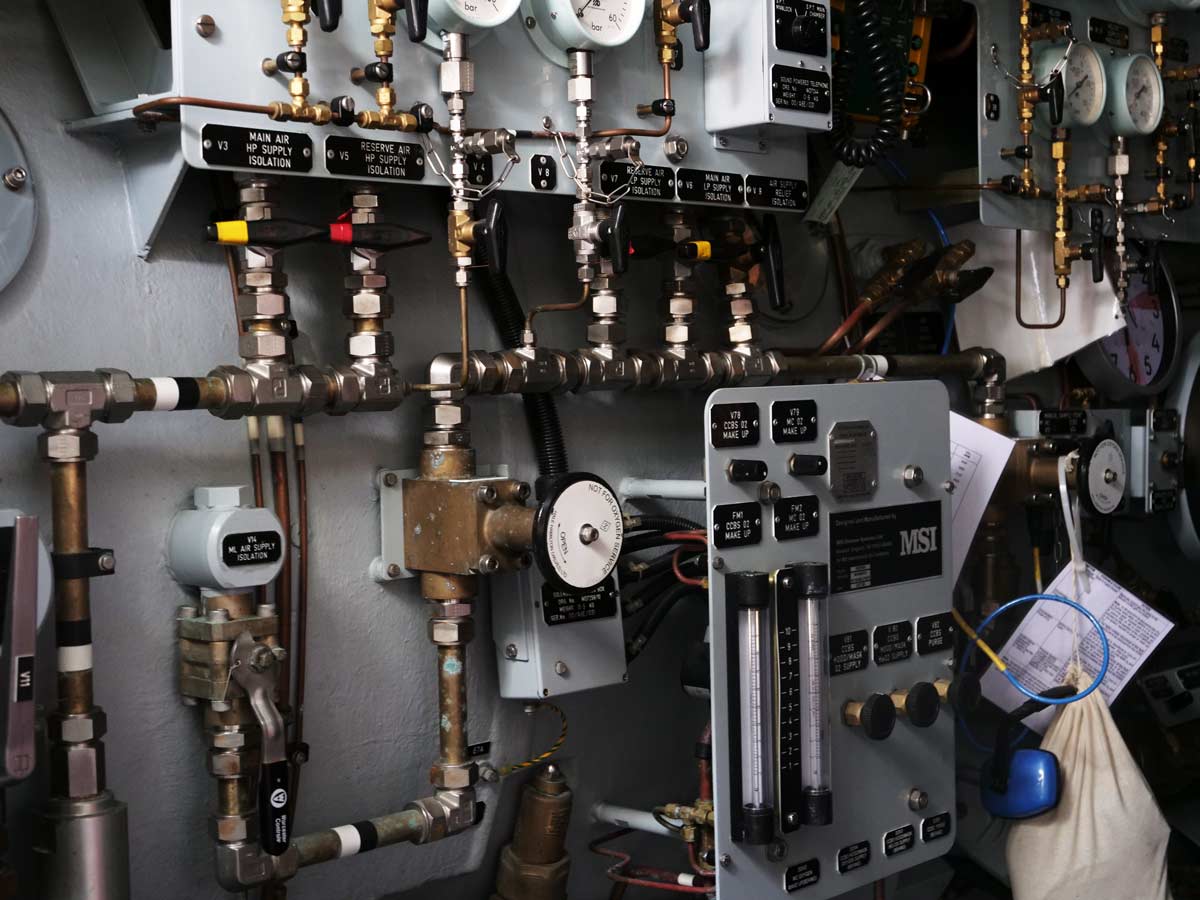

The Royal Navy’s Hunt class MCM vessel, HMS Cattistock (M31), was docked in the Thames for DSEI from September 12–15. First commissioned in 1982, when she’s not performing missions in the Gulf as part of the Royal Navy’s four-strong minehunting force permanently stationed in the region, HMS Cattistock is normally docked in Portsmouth. Despite talk of moving to an unmanned mine capability, I was immediately struck by the sense of pride the crew (HMS Cattistock has a total crew of 45) has in the ship and their belief that she will still be hunting mines for many years to come.

Like most of the Hunt-class vessels, HMS Cattistock has a hull made of Glass Reinforced Plastic, which aids sea keeping and conceals the ship’s presence from sea mines. In 2012, the eight Hunt class vessels underwent a mid-life upgrade, which saw HMS Cattistock fitted with two new Caterpillar C32 Acert diesel engines, which gives it about 15 knots. It has two propellers, two shafts and two rudders at the back, so for her size (60 m in length with a displacement tonnage of 625), she is incredibly manoeuvrable.

Hunt-class vessels like HMS Cattistock, were traditionally designed to perform mine sweeping—dragging a towed mechanical sweep behind the vessel—and minehunting, but currently, they are only configured to perform the latter function.

For mine detection and classification, the vessel is fitted with a hull-mounted high definition sonar, which is optimised for littoral waters and said to be effective against all mine types, including stealth mines.

Currently, the only ‘unmanned’ vehicles used by the Royal Navy’s MCM squadrons are the remotely operated REMUS 100 and 600 autonomous underwater vehicle for underwater surveillance and reconnaissance and the one-shot SeaFox mine disposal system.

The HMS Cattistock carries the SeaFox mine disposal system. The Royal Navy’s Mine Disposal System is based on two variants of the SeaFox: an explosive free recoverable Inspection vehicle or I-Round; and a live Warshot Vehicle or Combat Round, for identifying and disposing of underwater ordnance and sea mines. The SeaFox uses a shaped charge of 1.5 kg of high explosives taken from anti-tank munitions. The Royal Navy can run one mission an hour with the SeaFox.

The I-Round is used for training, route survey operations and wreck survey. HMS Cattistock carries two inspection rounds launched from the Sweep Deck. For inspection rounds, the SeaFox uses a fibre-optic cable from the mother ship.

In addition to the SeaFox, explosive charges can also be laid by mine clearance divers on board HMS Cattistock. Mine clearance divers are, according to some, said to be resistant to the proliferation of unmanned systems for mine clearance. One can perhaps understand why.

They are highly trained individuals, able to operate in various sea states and are rewarded by the work they do clearing shipping lanes, and keeping ships and their crew safe. They are also responsible for carrying out major engineering work on the ship’s propeller or hull if needed.

To move to a fully autonomous system for MCM would require the Navy putting all its faith in machines, instead of relying on the many years of experience and instincts of highly trained drivers.

At Unmanned Warrior 2016 off the west coast of Scotland, Atlas Elektronik’s ARCIMS unmanned surface vessel (USV), with a towed mine-hunting sensor, is said to have detected and classified mines more quickly than a traditional minehunter vessel, but it also produced a greater volume of data.

No one is suggesting that minehunting and disposal will become fully autonomous overnight. Most navies are contemplating a hybrid approach where a “mother ship,” which could be a traditional minehunter vessel or USV, will launch and recover unmanned systems carrying different sensors, which will enter the minefield.

Unmanned systems still need human operators who will be either shore-based (within a portable operations centre) or on board a host vessel (within the command centre) remote from the minefield. But, in future, are mine clearance divers going to be satisfied spending less time in the water and more time operating unmanned systems?

On a challenging day, a mine clearance diver could spend up to three days decompressing in the on-board compression chamber.

What is apparent from my visit to HMS Cattistock is that her crew still believe she has a good few years left in her yet as a traditional minehunting vessel, and as for the mine clearance divers, despite having one of the most physically demanding jobs in the Navy, they seem reluctant to hand everything over to the ‘robots.’

Photos by Anita Hawser