The Fallout From Brexit

Immediately following the UK vote to leave the EU, the pound declined in value, which is likely to impact the cost of already announced defence acquisition programmes and support costs for in-service equipment.

Stuart Young, Peter Antill and Richard Fisher

03 January 2017

Immediately following the UK vote to leave the EU, the pound declined in value, which is likely to impact the cost of already announced defence acquisition programmes and support costs for in-service equipment. But until Article 50 is triggered, the wider implications for UK defence and security, are unknown.

On the 23rd June 2016, the British electorate voted to leave the European Union (EU) , in what can only be described as a surprise result that has sent shockwaves through not only the British political establishment but across Europe and the rest of the world. As far as UK defence acquisition is concerned, a strategic environment that was already in a state of dynamic flux due to the publication of a new National Security Strategy (NSS) and Strategic Defence and Security Review (SDSR) in late 2015, was made even more complex by the referendum result and what that potentially means for the UK's international relations.

While the full impact of the Brexit vote is unlikely to be understood for some time to come—especially as the UK has yet to officially declare its intention to leave under Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty—we will look at some of issues and challenges that now face UK defence acquisition, in light of recent political events.

Bureaucratic roadblocks

The new SDSR was published in November 2015, only a few months after the election and it was soon apparent that while much of the preparatory work had been completed, there had been little strategic direction from ministers, who were focused on the election and not the SDSR. Unfortunately, this could prove to be an ongoing issue, with the UK Parliament now subject to fixed five-year terms, and coincidently, five-yearly defence reviews. The lack of strategic direction has been inadvertently exacerbated by firstly, the disruption caused to normal government business by the EU referendum campaign, and secondly, as a consequence of the result, which was swiftly followed by the resignation of the Prime Minister David Cameron, selection of a new Prime Minister (Theresa May) and the formation of a new cabinet, which has had to address the urgent question of negotiating our exit from the EU.

With regard to the UK's broader defence relationship with Europe, it has always seen NATO as the bedrock upon which that relationship rests. Joint defence acquisition has taken place on an ad hoc basis, through either bilateral (such as with France on the Sepecat Jaguar) or multilateral (such as the Panavia Tornado and the Eurofighter Typhoon) arrangements, away from organisations such as the European Defence Agency (EDA) or OCCAR—notable exceptions being the A400-M transport aircraft and Principal Anti-Air Missile System (PAAMS), as well as, potentially, Boxer.

Although there have been opportunities for the UK to increase its participation and even assume more of a leadership role with the resultant increase in opportunities for UK industry, the UK has seen the EDA and OCCAR as having a greater benefit to smaller countries and something of a bureaucratic roadblock as far as acquisition cycle times are concerned. For example, in October 2012, the UK Government announced it was reviewing its membership of the EDA, which didn't rule out the UK's complete withdrawal. Other issues, such as the creation of an EU 'Army' have been strongly opposed by the UK, as having the potential to undermine NATO and a duplication of effort, with the potential to push the US away from Europe. Hence, in defence policy terms at least, the UK has not been in favour of greater European integration.

SDSR 2015 THROWN INTO DISARRAY

There are many issues and challenges facing the UK Ministry of Defence (MoD) and armed forces as a result of the decision to leave the EU.

Budget

One consequence of the Brexit vote has been the fall in the value of sterling with regard to foreign currencies. For example, on the day of the referendum, the exchange rate (pound sterling to US dollar) was £1 to $1.4893. Immediately after the result became clear, the value of the pound plummeted, and despite several attempts at rallying, stood at £1 to $1.2422 towards the end of November, a drop of 17%.The instability in the exchange rate is likely to continue, with the most informal and unintentional statements by ministers involved having an impact.

Even before the referendum, the MoD was struggling to make efficiency savings to keep the Equipment and Support Plan affordable, including the planned renewal of the nuclear deterrent. What complicates matters is that according to US State Department figures (for the years 2002 to 2012), the UK has an established demand for importing defence equipment from the US. The figures include significant equipment purchases (such as C-17 aircraft and Predator Unmanned Aerial

Vehicles), but also spares related to US equipment operated by the UK Armed Forces. The figures also show that in general, the UK imports more than France and Germany combined and more than Saudi Arabia.

Furthermore, the UK plans to buy a number of off-the-shelf products from the US, including additional Apache helicopters, nine P-8 Orion Maritime Patrol Aircraft (MPA), 138 F-35B aircraft and 20 next-generation Protector UAVs, all of which will add to the yearly demand for defence imports from the US in terms of spares. Given the deterioration in the value of the pound against the dollar, this must represent a major financial challenge for the MoD.

It is a situation not helped by the weakening of the pound against the euro and where, for example, the British Army plans to acquire 589 Ajax vehicles for £3.5 billion, the majority of the costs of which, are in euros. However, if the contract was signed in sterling, then this would be a problem for General Dynamics, rather than the UK government. Even if the companies involved had bought extra spares and components in the lead up to the referendum, and the UK Government bought dollars in advance, these programmes will be running over decades, and it would be optimistic for the MoD to set up contracts on the assumption that the pound will recover to its pre-referendum level.

In his autumn statement, the Chancellor stated that the Office of Budget Responsibility (OBR) expects the UK economy to grow by 1.4% in 2017 (down from 2.2%) and 1.7% (down from 2.1%) in 2018. Therefore, a defence budget based on 2% of GDP will not grow significantly for at least the next couple of years. As such, the referendum has thrown the SDSR 2015 into some disarray. If the decrease in the value of sterling is sustained at the current level, the cost of the UK's defence exports will rise by at least £700 million per annum, as firstly, the amount of money spent on defence imports is unlikely to fall, given the continuing costs of supporting in-service equipment and secondly, due to the UK's commitment to purchase additional equipment such as the F-35B.

"With a defence budget of slightly more than £35 billion, the £700-million shortfall amounts to a 2% cut in the purchasing power of Britain's defence budget, and a much larger cut in the purchasing power of the equipment and support budgets." Clearly, the implications for UK defence acquisition of the devaluation of the pound are complex and will only become clearer with time. Such a devaluation makes UK exports that much cheaper, but it also increases the cost of any imported raw materials or components.

Regulation

One significant issue related to the UK's membership of the EU has been EU Directive 2009/81/EC (The Defence Procurement Directive), which requires the acquisition of defence equipment above a certain threshold to be competed across the entire EU. Although there are exemptions to this directive, covered under TFEU (Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union) Article 346, such exemptions are becoming harder to justify under national security terms. The UK Defence Industry (and the MoD) sees this directive as, at best, a delay in the procurement process, and at worst, a barrier to UK industry winning defence work. It could also be seen as a constraint on the UK's 'freedom of action' as a sovereign state. Whatever the result of the Brexit negotiations, if the UK chooses to remain within the European Free Trade Area, it will have to accept some of the constraints this imposes, such as Directive 2009/81/EC.

The opportunity that arises from the ability of the UK Government to determine its own procurement frameworks is enhanced by the similar ability to adjust other EU legislation, for example in the environment and safety sectors, to better suit the UK’s industry—all to be determined, at least initially, as part of the Great Repeal Bill.

Political Relationships

More difficult to quantify is the impact Brexit will have on political relationships, both domestic and foreign. With the majority of voters in Scotland (along with Northern Ireland and Gibraltar) voting to remain within the EU, there is an increased possibility that the Scottish National Party (SNP) will push for a second independence referendum, if its political demands vis-à-vis the EU are not met. If successful, this could have all the potential impacts that were envisaged before the 2014 referendum, especially with regard to Type 26 frigate construction and the Faslane submarine base, compounded with the strategic investment the government has identified for Scottish defence infrastructure, both from the relocation of capability within Scotland, but also the relocation from the rest of the defence estate to Scotland.

Externally, the willingness of other European states to continue their collaboration with the UK under ad-hoc bilateral or multinational programmes, once the UK has left the EU, could be open to question. For example, Slovakia holds the (rotating) EU Presidency until 31 December 2016 (after which it passes to Malta) and its Prime Minister, Robert Fico, has led calls to make the UK's exit from the EU as difficult as possible. This is likely to increase division within the EU as those states who want to 'punish' the UK clash with those who wish reconciliation.

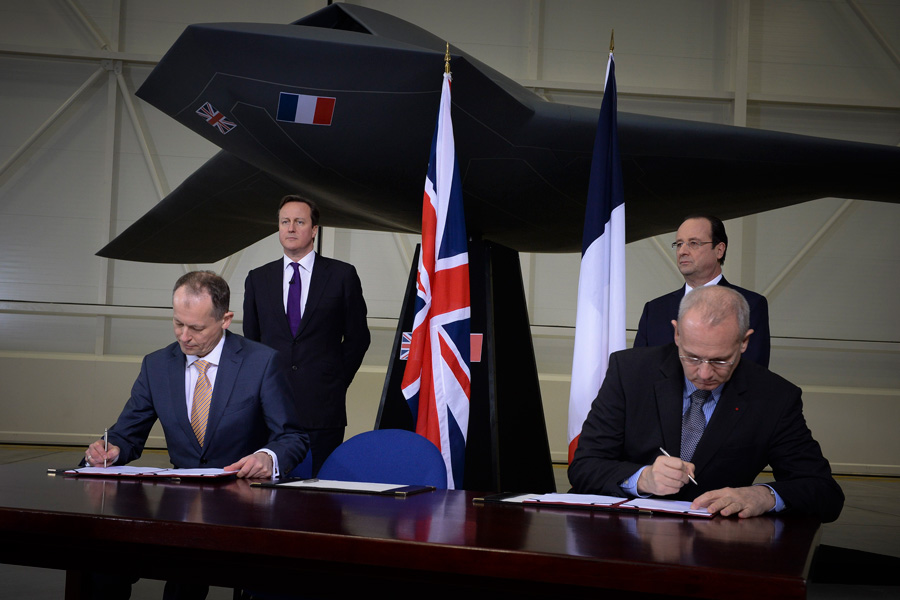

However, Brexit is unlikely to affect the Franco-British relationship, as this was cemented by the Lancaster House treaties in 2010, which included a nuclear cooperation agreement, thereby limiting it to just the UK and France, and both countries are committed to a number of defence projects, such as light anti-ship missiles and FCAS (Future Combat Air System). Even after leaving the EU, the UK "remains for the foreseeable future, France's most credible and reliable partner in the realm of defence on the European continent. The two countries share similar interests, which Brexit cannot affect", so it is important that France remains in the 'reconcile' camp.

Brexit, however, will certainly limit the UK's access to EU research funding. The strength of the UK economy as a whole, as well as its research base and defence industry, means that the UK will remain an attractive partner for other European states in terms of defence acquisition. However, given the UK's exit from the EU is still years away, one cannot know for sure what will happen. What will be important for the UK is how it uses the Brexit decision to recast its role in the world and redefine its identity within an international context, forging new relationships with other countries—prime candidates being Africa and Asia,the Commonwealth and Overseas Territories. Such an adjustment will also require the UK to decide just what sort of foreign, defence and security policies it wants and what sort of capabilities it requires to fulfil such a role.

The old Chinese curse, "May you live in interesting times" seems to be especially relevant at the moment, with the UK electorate voting to leave the EU, and the election of Donald Trump to the US Presidency. For UK defence acquisition, this means there is a great deal of uncertainty in the short-to-medium term, two of which have been highlighted in this article. Both have the potential to impact how the MoD operates and how it generates UK military capability. Only time will tell as to the true impact and consequences of Brexit.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS:

After retiring from the Royal Navy in April 2008, Stuart Young joined Cranfield University as Deputy Director of the Centre for Defence Acquisition. His research activities are focused on the government-defence Industry relationship and the associated risk management and decision-making processes. He also advises a number of governments on the development of defence industrial policy and strategy. He has undertaken a number of acquisition-related posts in the UK Ministry of Defence. He was the Electric Ship Programme Manager in the Defence Procurement Agency with direct responsibility for a major UK-French technology development programme.

Peter Antill works at the Centre for Defence Acquisition, Cranfield University, Defence Academy of the UK. He conducts research in defence acquisition and has written various books, journal articles, case studies, conference papers, monographs and chapters in edited publications as well as updating teaching material used by the Centre for Defence Acquisition. Peter graduated from Staffordshire University in 1993 with a BA (Hons) International Relations and followed that with an MSc Strategic Studies from Aberystwyth in 1995 and a PGCE (Post-Compulsory Education) from Oxford Brookes in 2005.

Richard Fisher is a research fellow in global defence acquisition at the Centre for Defence Acquisition, Cranfield University. He is focused on the defence industry and how its relationships impact on the product lifecycle and the acquisition process. After 10 years in local government and a short spell working in the defence industry on waste management issues, Richard moved into academia.