Survival of the Fittest

Cutbacks at BAE Systems highlights the challenges for UK defence companies as they navigate the uncertain world of defence orders.

Anita Hawser

13 October 2017

With the publicity surrounding BAE Systems’ announcement this week that it plans to cut approximately 2,000 jobs from its military air and Information and maritime workforce, one could be forgiven for thinking that this is an out-of-the-ordinary event. But haven't we been here before? It’s not the first time that the UK defence contractor has had to implement drastic cutbacks to its workforce in response to the ebb and flow of defence orders.

A break in construction between the Vanguard class and Astute class submarines saw BAE Systems’ workforce at its Barrow-in-Furness shipyard, fall to less than 3,000 at one point, which resulted in the loss of vital skills in submarine construction, which had a knock-on effect on the construction of the Astute submarines.

The question whenever there are cutbacks on this scale is will vital skills in the defence industrial base be lost forever? Given the long lead-in times for new orders of combat aircraft, submarines and ships to materialise, this is a risk that always exist if original equipment manufacturers (OEMs) are solely reliant on UK government defence orders to sustain their business.

Commentators believe BAE Systems has learned from previous experience and see the cutbacks as more of an attempt by the company to scale back production capacity in response to a decline in production orders for the Eurofighter Typhoon. Trevor Taylor, Professorial Research Fellow for Defence, Industries and Society at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), says BAE is making the cuts to ensure they maintain combat aircraft expertise. “They are very concerned about skills—BAE is very sensitive on that issue—to meet future demand.”

Taylor says there is general optimism about further orders for the Eurofighter Typhoon (BAE Systems owns a third of the consortium that builds the aircraft), but it is a question of where and when? In 2012, Eurofighter lost out to the French Rafale combat aircraft in a contract estimated then to be worth $10bn (£6.3bn) to supply jet fighters to India. The contract was later significantly scaled back by India from 126 fighter jets to just 36. At the time, however, the loss of the contract sparked rumours of significant job losses at BAE Systems, which the company denied. But in 2015, more than 300 jobs were lost at Warton where BAE manufactures the Typhoon.

“There is a huge amount of politics in acquisition decisions about combat aircraft,” says Taylor of RUSI. “It is not simply a question of value.” Qatar has agreed to buy 24 Typhoons and support capabilities from the UK. The two countries signed a letter of intent in September this year, but souring relations between Qatar and other Middle Eastern countries like Saudi Arabia, which also operates the Typhoon, could overshadow the deal.

In a statement released by BAE Systems, it said negotiations are progressing to agree a contract with the government of Qatar, which, if secured, would sustain Typhoon production jobs, and manufacturing well into the next decade. “However, the timing of future orders is always uncertain and to ensure production continuity and competitive costs between the completion of current contracts and anticipated new orders, we now plan to reduce Typhoon final assembly and Hawk production rates,” the statement said.

The Statement of Intent also mentioned Qatar's intention to acquire six Hawk aircraft. This is subject to agreeing a contract between BAE Systems and the Qatar government. BAE says it is actively pursuing additional orders which, if secured in the next year, would further extend Hawk manufacturing.

However, in view of the UK Government’s decision to take the RAF’s Tornado fleet out of active service in 2019, BAE says Tornado support and sustainment activities at RAF Marham and RAF Leeming will be progressively wound down and will cease at that time. Longer term, it says its presence at RAF Marham is underpinned by F-35 sustainment activities. “As a result of the above changes there is a total proposed reduction of up to 1,400 roles within the Military Air business across five sites, over the next three years,” says BAE Systems.

F-35 production at BAE Systems in Samlesbury is expected to ramp up by 2020 (Photo: MoD/Crown Copyright)

F-35 production at BAE Systems in Samlesbury is expected to ramp up by 2020 (Photo: MoD/Crown Copyright)

However, it says its Military Air UK operations will continue to benefit from the ramp-up of F-35 Lightning II production at Samlesbury to reach steady state production rates by 2020. BAE is responsible for manufacturing 10% of every F-35 aircraft globally at its UK operations. “…we continue to invest in the technologies, skills and capabilities that are critical to maintain our leading position in military aircraft design, engineering, advanced manufacturing and support,” BAE stated. The Eurofighter Typhoon is manufactured by a consortium of European companies (Italy’s Leonardo, BAE Systems and Airbus.) Components for the F-35 fifth-generation fighter jet are built around the world, but the OEM is US company Lockheed Martin.

UK VS. US DEFENCE COMPANIES

According to Taylor of RUSI, the F-35 is just one of many US defence products that the UK is spending money on. He also points to the P-8 Poseidon maritime patrol aircraft, and the Apache attack helicopter, both made by Boeing in the US. The UK has also acquired MQ-9 Reaper UAVs and its replacement, the Predator-B, from US company, General Atomics.

“A lot of the UK defence budget is being spent on overseas product,” he says, pointing to US State Department figures, which he says show billions of dollars worth of defence spending commitments a year from the UK to the US. “I can’t remember a time when there was such a level of commitment to US systems since World War II."

Taylor says a lot of these projects were in place before last summer’s Brexit referendum, but it begs the question how are UK defence OEMs likely to fare post-Brexit, given the UK’s desire to do more trade with the US, its second largest trading partner after the EU?

UK Ministry of Defence figures for 2016/2017 show that a total of £24.1 billion was awarded by the MoD Core Department to UK and foreign-owned organisations for competitive contracts.

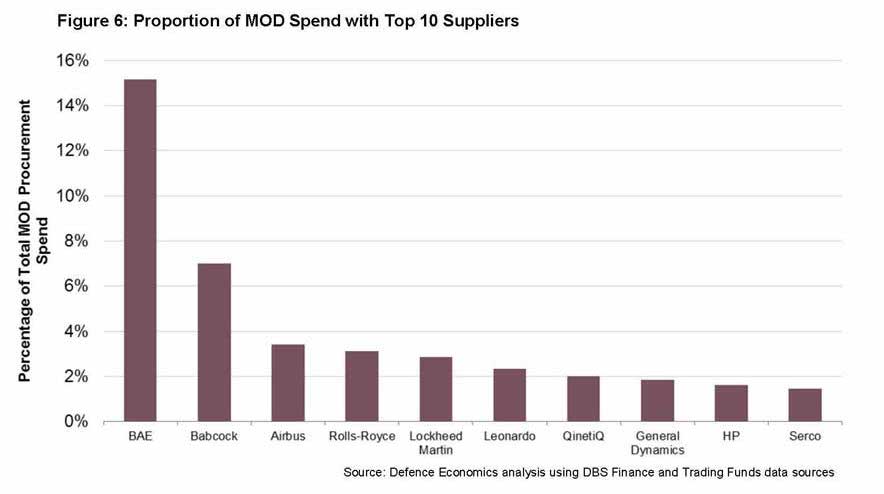

BAE Systems was the largest defence supplier in terms of annual spend made by the MoD in 2016/2017, a position which hasn’t changed in the past decade, according to the MoD. BAE received 15% of all MoD procurement expenditure in 2016/17. The remaining nine suppliers in the top 10 received individual shares of between 1.5% and 7.0%.

According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute figures, in 2015, BAE Systems was the third largest company in the world in terms of arms sales, behind the US’s Lockheed Martin and Boeing. The only other European company in the Top 10 in terms of total arms sales was Airbus; the remainder were US companies, which dominate international arms exports, with Russia and China increasing their market share.

A RENAISSANCE IN SHIPBUILDING?

Whilst BAE Systems is the biggest beneficiary of MoD defence expenditure, it is perhaps more a question of how much money is being spent, what it is being spent on, and the timing of major funding projects. In September, the UK government unveiled its National Shipbuilding Strategy, which outlines an ambitious investment programme in next-generation Dreadnought submarines; Type 45 destroyers; and a "phalanx of new frigates"—including a flexible and adaptable general purpose light frigate, the Type 31e—as well as the Astute class submarines and five new offshore patrol vessels.

Despite an apparent renaissance in UK shipbuilding, in its recent re-organisation announcement, BAE Systems also announced a reduction of 375 roles in its Maritime Services division, which it said were in response to evolving customer requirements and an ongoing focus on efficiency improvements.

Tayor of RUSI says the cuts to shipbuilding are tied into the MoD’s defence budget. He says the National Shipbuilding Strategy makes it clear that the MoD expects companies to find exports to fill the gaps between UK maritime orders. The first batch of five Type 31e vessels is expected to be in service by 2023. “But once the Type31e is built, what happens then?” asks Taylor.

The Type 31 will be designed from the outset as an “exportable vessel,” but when the ships required for the UK Navy are built, will there be enough export orders to sustain UK shipbuilding capability into the future? “There is pressure across the whole UK defence programme,” says Taylor, “which might make it difficult for UK defence companies to be too optimistic about the level of work that is going to be available.”