George Washington's Guerrilla Tactics at Trenton

George Washington suffered numerous defeats at the hands of the British. But by using guerrilla tactics, he altered the course of the American Revolution.

Peter Polack

07 December 2018

U

ntil his unconventional victory at Trenton in December 1776, George Washington, the founding father of the United States of America, had incurred a series of losses both on the battlefield and of political confidence in his leadership.

The first and largest battle of the war against the British took place in August 1776 in Brooklyn, New York, also called the Battle of Long Island, which saw the Revolutionary Army bested by a professional force led by experienced and determined officers. The British Army had several centuries of development proven in many wars and was a formidable force in which overconfidence naturally prevailed in the war of the American Revolution.

Trenton was a real guerrilla action in which a military leader, classically trained, sought to strike against a fixed military position, which in its genre, would have resulted in retreat if faced with firm opposition or capture of the target. George Washington chose a plan to be implemented in a manner and at a time not seen before in the revolutionary conflict, which was destined to catch the opposing elite force of German mercenaries by surprise and eventually, mean defeat of the Hessians.

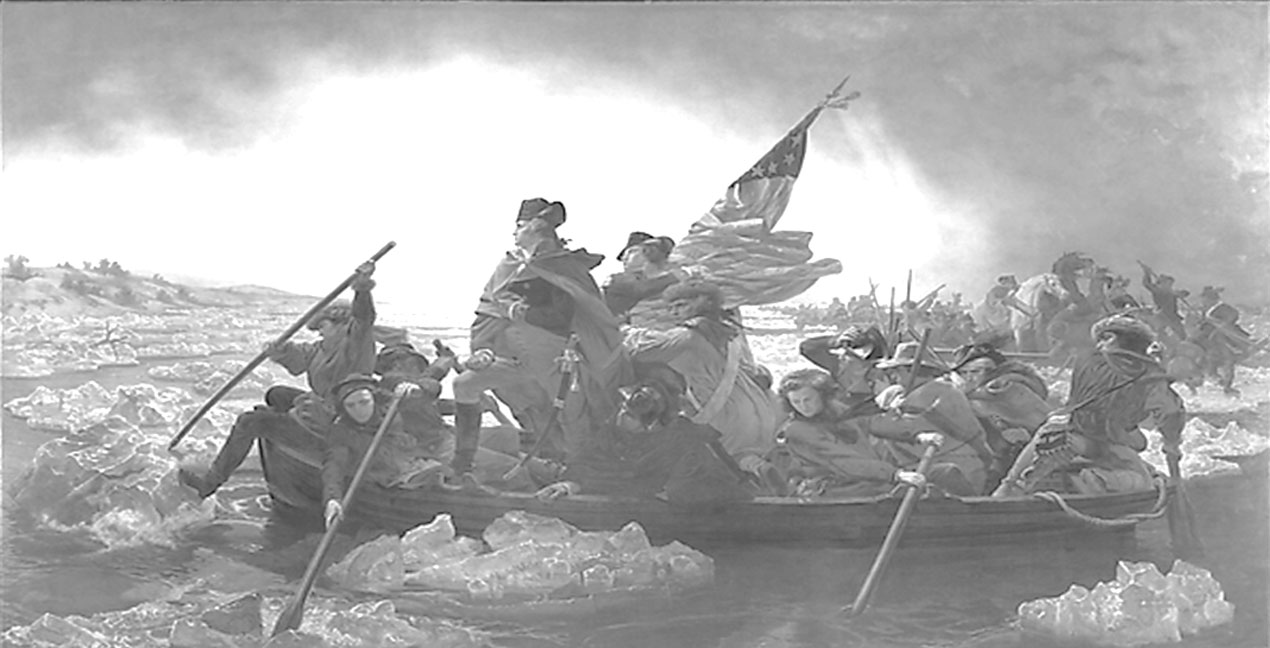

The plan was simple in concept and entailed the movement of several thousand soldiers across a swift, wide, ice-ridden river to face an encamped enemy half their number, at night, on Christmas Day, accompanied by three times the artillery compliment of the target, in the dead of winter.

Washington had his force of over 2,000 men and 18 pieces of artillery mustered at dusk to begin a Christmas-night crossing of the Delaware River from Pennsylvania into British-held New Jersey, across a flowing waterway beset with large floes of ice that could crush or sink a boat. Among the many vessels used for the event were long, short draft Durham boats capable of carrying many tons of cargo crewed by Massachusetts sailors from Marblehead.

Various delays, including worsening weather, saw Washington's forces cross just nine miles north of Trenton in the early morning. Washington nevertheless pursued the attack and divided his force into east and west elements for an encompassing attack on the slothful, but still dangerous, Hessians.

The Trenton attack force had a key commander in Colonel Henry Knox who secured the crossing of men and cannon before proceeding to Trenton where artillery was strategically placed and moved, when necessary, to command the open streets. The Hessians were unable to launch a significant counter-attack or reduce themselves to small roving irregular bands under the Germanic military theory prevailing at that time.

In general terms, heavy and slow artillery had not been part of the guerrilla arsenal ,but used and discarded after capture as part of an overall strategy, or retained if desired for the rare occasions of securing base territory gathering points. Over time, artillery was replaced by ubiquitous rocket propelled grenades, wire guided anti-tank mobile missiles or shoulder fired anti-aircraft missiles and more recently, vehicle-borne explosive devices.

On 26 December 1776, Washington led his men to the first encounter with a Hessian outpost, a mile from Trenton, when there was an exchange of gunfire before they fled to Trenton to warn their companions of the American assault. Washington dispersed his men and cannon at key points, ironically at King and Queen Streets, the very spot Rall had contemplated but omitted to establish an artillery emplacement. The disciplined Hessians repeatedly retreated, returning fire and receiving cover fire from other soldiers as they went towards the north end of Trenton.

Colonel Rall, who took command after some delay, got his men to come up the streets to overcome the rebel artillery, but this failed at every attempt due to the volume of fire from the American rebels, and even some citizenry, from the protection of buildings along the open streets. The Hessians then faced an overwhelming attack of men, musket shot and cannon fire, which led to the capture and abandonment of the Hessian cannons, forcing a full retreat to the rising open field to the north of Trenton where Rall got his men to form proper lines to counter-attack. Some Hessians fled the area completely in a wild melee to reach safety and evade capture.

The Hessians broke and fled to a nearby orchard having incurred about 100 casualties, which only increased their demoralised stance as they faced abject defeat in North America for the first time. German speaking members of Washington’s raiding party shouted out to the Hessians to surrender, which they eventually did in acknowledgement of the futility of further conflict. The captives were nearly 1,000 in number with a dead commander, many dead officers and all their arms, artillery and supplies seized by the rebel army.

Washington had secured his first victory, which started a reversal of fortune for the British in its American colonies, which culminated at Yorktown in 1781, with the aid of French assistance to the American Revolution. Naysayers of the D-Day casualties to liberate France and Europe should remember this. Some may think that the decimation of the Hessian force was a better outcome for the American cause, but a thousand examples of defeated Hessian soldiers marching through Pennsylvania to Philadelphia, and in some cases deserting to the rebel side, was invaluable to Washington.

This excerpt is the second in a series taken from Peter Polack's latest book, Guerilla Warfare: Kings of Revolution, released in October 2018 by Casemate Short History. To find out more about the book, click here.

END NOTES

1. Michael Lee Lanning, The American Revolution 100, Sourcebooks, 2008, 32

2. David F. Burg, The American Revolution, Facts on File, 2007, 150

3. Anthony H. Cordesman, Iraq’s Insurgency and the Road to Civil Conflict, Prager, 2008, 587

4. Ian Barnes, The Historical Atlas of the American Revolution, Routledge, 2000, 86-87