William Wallace, the Original Guerrilla Fighter

Guerrilla Warfare: Kings of Revolution, William Wallace was a virtual unknown before he rose up to defeat the British at the Battle of Stirling Bridge.

Peter Polack

07 November 2018

What was most extraordinary about the guerrilla leader William Wallace was the speed in which a virtual unknown rose up to national leadership and the short time between his first action; the killing of the English Sheriff of Lanark in May 1297 and his victory at the Battle of Stirling Bridge on 11 September 1297, a mere four months later.

Even more compelling was that within a year, Wallace had ceased his position as Guardian of Scotland in favour of Robert the Bruce, the future King of Scotland, before disappearing until capture and vile execution on the orders of King Edward 1 of England in 1305; only eight years between rise and demise.

Perhaps Reverend J.S. Watson said it best: “If there has been any exaggeration of his merits, in narratives oral or written, in subsequent days, it must still be believed that he would never have become such an object of panegyric among his contemporaries, unless he had signally transcended other men.”

The conflict that gave rise to the emergence of William Wallace was a dispute over the throne of Scotland between Baliol and Robert the Bruce that led, after some maneuvering by King Edward 1 of England, to war and the submission of Baliol who had aligned himself with the French. In the end, King Edward, also known as Longshanks, for his height, carried away the Scottish throne of stone from Scone and destroyed records pointing to Scottish independence or the inferiority of the English. After Baliol spent a period in the Tower of London, he was exiled to France where he died.

Very often a guerrilla leader will arise in circumstances of political turmoil such as conflict on the succession to a throne, the opposing forces of a civil war on the cusp of independence such as China or Angola, or the ethnic Balkanisation of Sri Lanka.

Edward then appointed a Governor-General of Scotland and filled as many posts as possible with English immigrants, a template adopted by England throughout the ages to this day in their few tiny remaining far flung possessions.

The original Governor-General soon vacated the post leaving the ruthless Chief Justice Ormesby and Lord-Treasurer Cressingham to oppress and loot Scotland, a historical mandate repeated throughout English possessions for centuries. Edward then ordered a further requirement that the landed gentry of Scotland swear allegiance to him under penalty of imprisonment or becoming a fugitive, which added to a growing resentment and hatred of the English occupiers.

Here, one of the primary elements of successful guerrilla warfare presented itself, when indigenous people have their land occupied by a foreign or local group that proceeds to regulate and often exploit a newly created and previously peaceful underclass.

The guerrilla leader often begins from nondescript and forgettable beginnings in the context of a single incident before beginning a climb to ultimate leadership. For George Washington it was Trenton, for Mao the Long March and King Ibn Saud, the capture of Masmak Fort in Riyadh.

The author A.F. Murison in his 1898 book originally published as Sir William Wallace describes a series of events at Chapter Three under the title, Guerrilla Warfare and quotes William Shakespeare in Henry IV: “Now, for our consciences, the arms are fair, when the intent of bearing them is just”.

All accounts tend to culminate with Walker's participation at the Battle of Stirling Bridge, preceded by what is often referred to as the rising in Lanark after the killing of the Sheriff. At this time, Wallace who came from a background of some privilege and connections ,was a fugitive from the authorities, not unlike the situation of former political fugitive and later Vietnamese General Vo Nguyen Giap in 1930. They were both strong nationalists that ended up in wars of independence, with Giap having the more eventual success.

Shortly after Lanark, anti-English forces within Scotland attracted by the small but bold actions of Wallace, some with petty axes of their own to grind, joined up with Wallace where they proceeded to roam central Scotland in sufficient numbers to win all encounters.

At the time, all of Scotland north of the Forth river was depleted of occupation by retreat of the English from attacks by Scots, except for Dundee and Stirling which drew the attention of Wallace and his followers to march for a siege on Dundee in August 1297. The Scottish forces, as was common at the time and seen even in present day Syria, was an alliance of forces, some with different agendas.

The joint force was under the leadership of Wallace and Andrew Moray or Murray which was confirmed by the Lubeck letter sent in both their names as leaders of Scotland. The Forth was a barrier to the north-east and Stirling was a critical geographical junction for any English army wishing to march on Scotland.

A guerrilla leader draws on small initial successes to gather confidence and spread his fame across the country, which is a double-edged sword. The benefit of attracting material support and fighters, but increased attention by the prevailing authorities, will limit general anonymity or traveling to further the cause. As the resistance group increases, so does the number of the hierarchy, which impairs command and control by single decision-making.

Wallace halted at the small abbey of Cambuskenneth in a village close to Stirling castle, surrounded on three sides by the river Forth across which the English encamped preparing for battle.

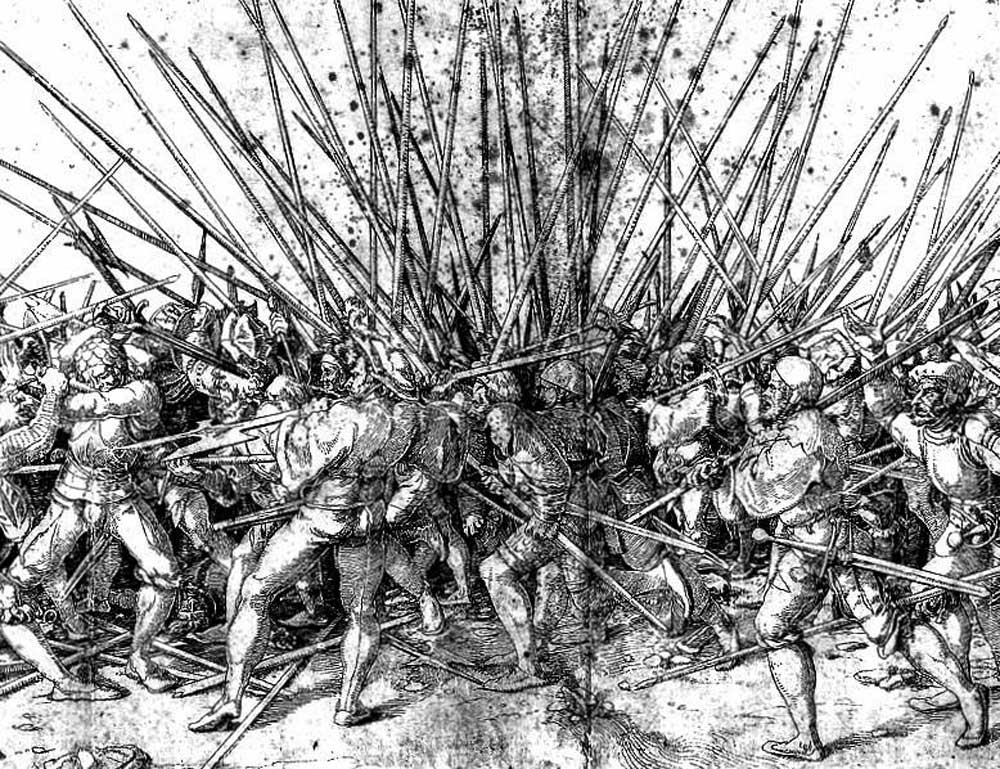

Wallace would later deploy his most significant anti-cavalry weapon at Falkirk, the schilitron, a large circular mass of men holding long spears or pikes often bound by ropes to repel horse-borne fighters, similar in appearance to a giant hedgehog.

This excerpt is the first in a series taken from Peter Polack's latest book, Guerilla Warfare: Kings of Revolution, released in October 2018 by Casemate Short History. To find out more about the book, click here.

END NOTES

1. G.W.S.Barrow, Robert Bruce and the community of the realm of Scotland, University of California Press, 1965,117

2. Reverend J.S.Watson, Sir William Wallace, The Scottish Hero: A narrative of his Life and Actions, Saunders, Otley and Company, 1861, 205-209

3. Brenda and Brian Williams, Kings and Queens, Jarrold Publishing, 2004,71

4. Reverend J.S.Watson, Sir William Wallace, The Scottish Hero: A narrative of his Life and Actions, Saunders, Otley and Company, 1861, 2

5. A.F. Murison, Sir William Wallace, Edinburgh: Oliphant, Anderson and Ferrier, 1898

6. Reverend J.S.Watson, Sir William Wallace, The Scottish Hero: A narrative of his Life and Actions, Saunders, Otley and Company, 1861, 156

7. Cecil B. Currey, Victory at any cost, The genius of Viet Nam’s Gen. Vo Nguyen Giap, Potomac books, 1997

8. A.F. Murison, William Wallace Guardian of Scotland, Dover Publications, 2003, 85

9. George Bruce and Paul H. Scott, A Scottish Postbag, Eight Centuries of Scottish Letters, The Saltire Society, 1986, 1