When The UK Made Military Small Arms

There was a time when gun design and manufacturing flourished in the UK and guns were exported to battlefields in India and America.

Anita Hawser

24 January 2019

At one time, the UK maintained more than 40 Royal Ordnance Factories (ROFs) for explosives, rifles and engineering. The most noteworthy of these were the Royal Small Arms Factory (RSAF) at Enfield, known locally as the “Gun Factory,” and the relocated Nottingham Small Arms Factory (NSAF), successor to the RSAF on the latter's closure, which was the last small arms factory in the UK to be closed in 2001.

Prior to the establishment of the RSAF and ROFs, private gun makers monopolised British gun production right up until the late 1850s. The RSAF in Enfield was established to address what some termed “a chronic lack of serviceable weapons” during the Napoleonic War.

Although the factory was completed in 1816, it was not until the 1850s that it was in a position to produce large enough quantities of weapons to service the British military after mechanised machinery from the US was installed. By 1860, the factory was producing more than 90,000 rifles, or 1,744 a week.

Some of the more noteworthy arms RSAF Enfield designed and/or manufactured include the muzzle-loaded 1853 Enfield Pattern musket, which used the Minié ball. The Enfield Pattern musket was widely used by the British during the Crimean War and by Confederate ranks during the American Civil War.

Other arms included, the Snider–Enfield Rifle: an 1866 breech-loading version of the 1853 Enfield; the Martini–Henry Rifle: a breech-loading lever activated rifle, manufactured from 1871-1891; and the L1A1 Self Loading Rifle (SLR), which was a British variant of the Belgium-designed FN FAL, the predecessor to the British Army's much-maligned SA80.

ROF Nottingham was established during the First and Second World Wars to support arms production. But once the war had ended, a number of these sites were closed. By the 1960s, parts of the Enfield operation were no longer functioning. In the 1980s, RSAF Enfield and other government ROFs were privatised and acquired by BAE Systems, who closed and sold the Enfield site in 1988 for commercial and domestic redevelopment.

THE AGE OF NATO

From the 1950s to the 1970s, ROF Nottingham survived by taking on specialist vehicle projects (the Centurion tank rework, Bloodhound missile launchers, tank ordnance). But as Jonathan Ferguson, Keeper of Firearms & Artillery at the National Firearms Centre in Leeds explains, private owners found it difficult to make a go of small arms manufacturing, which he attributes to a number of factors.

“State arms manufacturing facilities like Enfield, Springfield in the US or Saint-Étienne in France, were subsidised by their governments in order to maintain an indigenous capacity in case of war,” he says. “With the rise of NATO, that became less crucial; nations are now inter/co-dependent on each other for defence and industrial capacity. Unless these arsenals are able to find significant export or civilian sales, they are not sustainable in the modern economic climate.” In the UK, the domestic market for firearms is limited due to legislation, and boasts a relatively small shooting community, says Ferguson.

During the Second World War and the 1950s, says Ferguson, Enfield relied increasingly upon designers from Czechoslovakia, Poland and Belgium, who eventually returned home, leaving something of a capability gap. Whereas the UK excelled in other areas such as aircraft and vehicle design and manufacture, the private sector for small arms remained small. “Sterling, Enfield's only real rival in the field, struggled to remain commercially viable,” he explains. “Their most successful product was the 1944 vintage Patchett-Sterling sub-machine gun, which lost sales to the German MP5 and Israeli Uzi. Sterling’s factory closed in the late 1980s.”

By the time the British Army's standard issue SA80 rifle project, the replacement for the Enfield manufactured, Belgian-designed L1A1, commenced in the 1980s, much of the UK’s capacity for small-arms design and production had already been lost. “This had an impact upon the original ‘A1’ iteration of the SA80, resulting in the need to bring Heckler & Koch (then UK-owned) on board,” says Ferguson.

An early introduction of what had become the L85A1 Individual Weapon (IW) and L86A1 Light Support Weapon (LSW) into service led to a plethora of problems, and it was not until a multi-million pound upgrade programme was undertaken in the late 1990s that the L85A2 IW variant received largely unreserved user approval. Upgrade work was carried out in Germany by Heckler & Koch, which was briefly been owned by BAE Systems.

THE PATTERN ROOM

One legacy of the UK's small-arms manufacturing history lives on, however, in the form of the Pattern Room, which technically no longer exists as it is now housed at the National Firearms Centre in Leeds and forms part of the Royal Armouries.

The Pattern Room had its origins in RSAF Enfield and its production of the “new Pattern 1853 rifle for general issue to the infantry,” writes Peter Smithurst, Curator Emeritus at the Royal Armouries. Smithurst says the rise of RSAF Enfield as the main centre for the production of small arms for the British military meant the decline of the Tower of London as an arms manufacturing facility.

The term “pattern,” stems from the 17th century when King Charles I introduced the concept of “reference patterns” for military hardware. “It is from this time that the concept of the 'Sealed Pattern' evolved,” writes Smithurst. Any equipment accepted into military service would have affixed to it in some manner a red wax seal to denote that it was the 'reference standard.' When the factory at Enfield became operational, a special room was set aside to store newly created sealed patterns, hence it became known as the 'Pattern Room'.

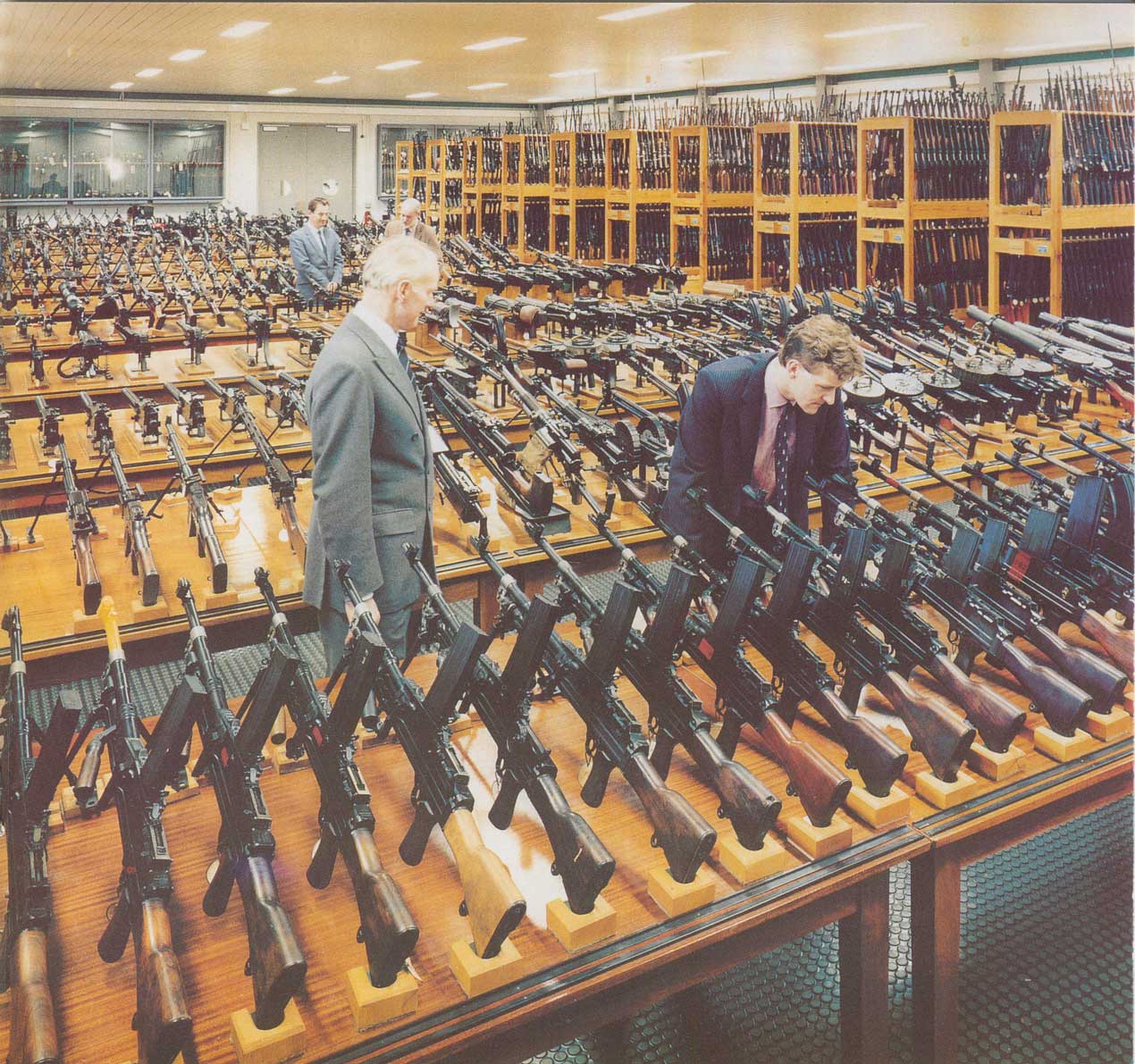

“As a worldwide collection of arms, the Pattern Room is a working reference collection, which covers the full range of international weapon development, including war trophies and experimental weaponry,” explains Richard Jones, the last Custodian of the Pattern Room and former Editor of Jane's Infantry Weapons yearbook, after it was moved from RSAF Enfield, which closed in 1988, to the site of ROF Nottingham.

Although the Pattern Room was originally intended as a reference facility, it has evolved to perform a range of functions, including the loan of weapons to the military for live firings and familiarisation. The extensive collection also assisted law enforcement and national security agencies by providing “comparative examples.” The collection is also a unique reference source consulted among others by documentary filmmakers, authors and antique firearm collectors.

While Custodian of the Pattern Room at ROF Nottingham, Jones says it was established practice to procure the first weapon to be produced from the initial production run of a new small arm entering service. Development of the collection to meet wider customer demand included support of forensic activities arising out of the events occurring in Northern Ireland from the late 1960s onwards. “While serving at that time in Northern Ireland, if we forensically recovered an unidentified bullet fired by terrorist groups, we used the Pattern Room to research which weapon it may have been fired from,” Jones explains. “That helped us narrow it down to one or two likely types of (new) weapon which had come into use in the province.”

He also used his time as Custodian to enhance the collection of Kalashnikov variants into one of the most comprehensive of its type, which is now used to determine the provenance and point of origin of weapons and ammunition used by non-state actors such as terrorists.

To this day, out of all the weapons he procured for the Pattern Room, Jones says the "AK" series, which he describes as the “Land Rover” of the military world given its ruggedness and durability, is still his favourite. “You can introduce something else, but it wouldn't necessarily be any better than the present day model,” he says, adding that the Russians have sought to replace it in recent years, but failed..”

By the mid-199os, however, the Pattern Room's future hung in the balance. Following negotiations between the MoD, who no longer saw the collection as a "core activity" and wished to dispose of it, and the Department of Culture, Media and Sport, the Royal Armouries, Britain’s National Museum of Arms and Armour in Leeds, said they would take the complete collection and continue to provide an all important service to what has been termed the official "user community".

After being placed in deep storage at a secure military base for three years following the early closure of the ROF Nottingham site (again for commercial redevelopment) in 2001, the Pattern Room's entire collection moved into its new home at the National Firearms Centre in Leeds in 2005.

The bringing together of the Tower Armouries, aka the Royal Armouries —which contained firearms for sport and hunting, in addition to military weapons —along with the Pattern Room, created what Smithurst describes as the largest and most comprehensive single collection of firearms and related material in the world, containing in excess of 25,000 items, spanning everything from 17th century muskets, to a rare Swiss Mondragón rifle and an early Luger pistol. “In many ways, it was the reuniting of two halves of the same collection — a circle that had been completed after 150 years,” wrote Smithurst.